What strategies are needed to survive the emotions that may follow the roadmap out of lockdown?

- Dr. Mia Eisenstadt

- Apr 6, 2021

- 9 min read

In the UK, COVID-19 restrictions have begun to ease from March 8th, 2021 after a punishing 3rd lockdown during the British winter. The new roadmap has plotted a path to removal of all legal limits on social contact in England by the 21st of June. In the oncoming months of gradual easing, what might the mental health landscape post-lockdown look like? What emotions may be likely? What evidence-based strategies might help with the emotions of transition and coping with the profound changes that the pandemic has brought?

My name is Mia Eisenstadt, I’m a writer and researcher at The Evidence Based Practice Unit and Paradym. My research over the past 4 years has focused on the lived experience of stressors and understanding the protective factors that reduce the harmful effects of stress and bolster resilience. My interest in blogging during the pandemic has been to raise awareness of mental health during COVID-19, as well as to bring attention to those groups that may struggle more in these uncertain times, or belong to communities that have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic, such as BAME communities and minoritised groups. I’m particularly interested in the diversity of experience. For example, for many people the lockdown has been difficult and challenging, but for others, it’s been an opportunity to stay at home and focus on the things they love doing. My previous blog focused on the topic of the way that stress affects young minds.

In this new blog, I discuss some possible emotions that may arise in the transition out of lockdown. I offer existing evidence-based strategies that may help with a possibly bumpy, and certainly gradual, transition.

Direction of travel: The roadmap for lifting lockdown

Whilst the transition out of lockdown is a welcome change for many, it is not a clear trajectory towards normalcy. It is difficult to say that the ‘R’ (the average number of people I would infect if I were to be infected with the COVID virus) will continue to go down until the summer and into the winter. Whilst the outlook is optimistic, scientists are keen to emphasise that careful observation is needed to check that the R won’t leap up again following opening up of public places and large events. It’s possible that it is not a linear path and there could be setbacks. Sage member Professor Andrew Hayworth has cautioned that it’s difficult to accurately predict.

Many of us, who have not booked holidays or attended gatherings with friends and family for some time, eagerly await the chance to make fun plans and attend special events and trips. Such plans bring hope, eager anticipation and positive feelings that stems from seeing family, having a hug with a loved one, social meet ups, holidays, day trips and many of the aspects of life that lead to a lot of excitement and joi de vivre.

Planning positive activities is proven to improve mental health and increase feelings of happiness and wellbeing. In fact, a number of evidence-based mental health therapeutic approaches encourage people in therapy to organise positive activities to support their mental health, enhance social connection and improve quality of life.

Things to look forward to are needed to provide hope in a context where many grim changes have resulted from the pandemic. The rise in anxiety, depression and distress in both children and adults is well documented world over. Increased substance use, and particularly alcohol consumption has become a major problem. In the US, younger adults, people from BAME communities and essential workers reported increased alcohol intake and suicidal ideation.

The far-reaching effects of the pandemic

The pandemic has brought in drastic ruinous economic and social changes such as unemployment, business failure, poverty, a rise in reliance on foodbanks, distrust of government and science and increased uncertainty.

Whilst there are many positive prospects of moving out of lockdown and the vast coverage of the vaccine roll out in the UK, there remain a number of unknowns.

Will I need to get a vaccine regularly, annually? What do I do about my aunt that does not want to get the vaccine? Will I need a vaccine passport? Will there be new mutations? Is the pandemic a blip or here to stay?

The number of uncertainties about the future has drastically increased.

A context of uncertainty, lockdown restrictions and increased risk of exposure to Covid-19 is a fertile ground for increased worry and anxiety.

Fortunately, there are a number of approaches from psychology that can support the reduction of worry and anxiety. Here, I’ll discuss two approaches: emotional reasoning and mindfulness.

Emotional reasoning

Four years ago I was in a car accident. Luckily neither myself nor the passengers in the other car were badly hurt (my car came to the end of its life). It was terrifying and ever since I am a nervous driver, specifically on four-lane British motorways. Whilst any driver would agree that four-lane motorways require caution and careful driving, they do not require sweaty palms and racing thoughts.

My stress response on a four-lane motorway resulted from my perception that they were more frightening than they are in reality and my thoughts could be described as reasoning from my emotions. If I noted my emotions and take steps to make myself feel safer, I will feel better. If, however, I suddenly reached conclusions about four-lane motorways that may not be true- this would constitute emotional reasoning, a common type of cognitive distortion (an unhelpful thinking style).

Emotional reasoning is where a person assumes that their own experience or emotional reaction to an event defines the nature of the event itself.

There are many instances where our emotions can influence our accurate perception of the situation.

Part of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) involves learning to separate thoughts and emotions and stop an internal narrative forming that is based on emotion, rather than objective fact. In the context of new vaccines and the uncertainty about the virus and its possible variants, it’s possible to fall victim to emotional reasoning. When being separated from particular friends and family for a long time, it’s possible to draw negative conclusions stemming from months or even a year of separation. From a CBT perspective, it would be advantageous to check individual assumptions before reaching any conclusions about the nature of a relationship after lockdown.

With the emotion of missing others and fear of missing out (FOMO), it’s possible to misinterpret others’ behaviour. However, via considered questions and seeking answers as it’s likely friends and family reciprocate the longing that is part of separation.

The end of lockdown may bring some intense emotions. The highs of being able to have a BBQ with family, attend a party or take a long-desired trip. The lows of the changes in relationships, jobs, mental health or even the wider social landscape. Many people have moved house or moved across the country. More people are suffering from symptoms of anxiety and depression. Some continue to struggle with long Covid. Some people have experienced positive events, such as a wedding or a book launch, other’s are bereaved and have struggled to grieve during lockdown or have suffered a massive loss of income, such as many musicians and artists.

There is a vast range of possible emotions, from elation to despair, as we both collectively and personally navigate out of lockdown. Emotions that may be influenced by a likely inevitable aspect of social comparison perhaps compounded by the fact that our lives are increasingly mediated by the internet.

What strategies help with managing emotions?

“Mindfulness has been described as the practice of “bringing attention and awareness to one’s momentary experience with a sense of acceptance and non-judgment” — (2017, P. 109)

Whilst mindfulness is currently well known in the West, the philosophy and practice originates from the East. In a western context, mindfulness was introduced by Jon Kabat-Zinn who founded a university-based Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction programme in 1979. Mindfulness originates from Indian Buddhist, Tibetan Buddhist and the Japanese Zen practise of Zazen (“sitting meditation). A more in-depth view of mindfulness can be found here.

Mindfulness requires attention to the present moment and task at hand. This can be counter current to our current Western culture where multi-tasking is the new norm. This is common in the pandemic, where the boundaries between work, home life and socialising can blur. Technology can enable us to do many things at once that can be both empowering but serve to divide our attention and potentially have negative effects on our memories.

In a therapeutic context, mindfulness has been applied in a range of approaches such as mindfulness-based stress reduction or mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT). This often involves group meditation and support and individual practice at home.

In a non-therapeutic or self-help context, mindfulness can also be performed at home and there are a range of videos, and apps online that can teach users the basics of the mindfulness practice. The neuroscience of mindfulness is explained in this blog.

Some of the concepts of mindfulness can also be applied to everyday life

A mindfulness approach would suggest being fully present to what we are doing (not focused on past or future), whether that is doing the washing up or listening to a partner or a friend.

“If while washing dishes, we think only of the cup of tea that awaits us, thus hurrying to get the dishes out of the way as if they were a nuisance, then we are not “washing the dishes to wash the dishes.” What’s more, we are not alive during the time we are washing the dishes. In fact, we are completely incapable of realizing the miracle of life while standing at the sink. If we can’t wash the dishes, the chances are we won’t be able to drink our tea either. While drinking the cup of tea, we will only be thinking of other things, barely aware of the cup in our hands. Thus, we are sucked away into the future -and we are incapable of actually living one minute of life.” — THÍCH NHẤT HẠNH, THE MIRACLE OF MINDFULNESS

So, does mindfulness work to improve mental health? What is the scientific evidence?

In research, in order to understand how effective an intervention or drug is, researchers pool together the quantitative results of different clinical studies to understand how effective a particular approach is overall based on data from a range of studies. This type of research is called a meta-analysis. Evidence gathered via a meta-analysis is much more powerful than via individual studies and considered the gold standard of scientific research.

In the case of mindfulness, a number of meta-analyses have been conducted to understand the effects of mindfulness programmes. In one meta-analysis of the effectiveness of mindfulness-based therapy, effect size estimates suggested that it was moderately effective for reducing anxiety and mood symptoms when comparing the mental state of participants at the beginning and end of the programme. In a more recent meta-analysis of the effectiveness of standalone mindfulness (not in a therapeutic intervention), the authors found it had a small and medium effect on lowering anxiety and depression.

Why is mindfulness relevant to coming out of lockdown?

Lockdown for many of us has involved dealing with feelings with a reduced range of coping strategies available to us due to living within four walls. There has been a rise in drinking alcohol and domestic violence that could be interpreted as poor coping with the stressors of the pandemic and being confined to a home.

Maladaptive and adaptive coping

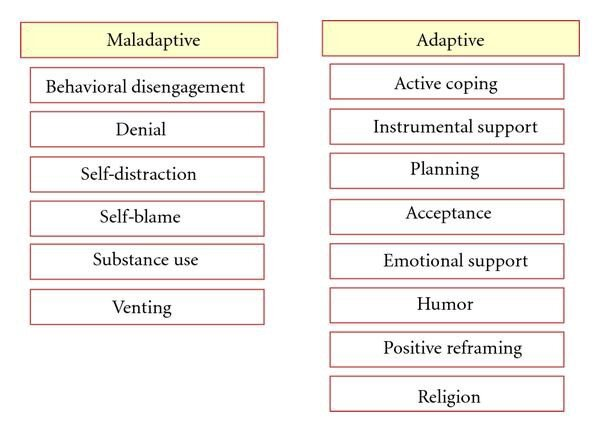

Coping with stress can be broadly divided into two types, maladaptive (unhealthy) and adaptive (healthy) coping. Adaptive coping helps us to respond to a stress and may even “fix” the stress (such as resolving a conflict, or extending a deadline). Maladaptive coping might numb or distract us to the effects of a stressor (such as drinking our troubles away), but does not change the stressor itself, and may add new stressors as the same stressor is present as the effects of the alcohol have worn off.

Understandably, with reduced access to things to do and access to support, such as people to hug and talk to, possibly most of us have had some experiences with maladaptive coping during lockdown. This may have involved drinking too much, eating too much or too little, ruminating over a topic, or not reaching out for support when we needed it.

Mindfulness can be added to our menu of coping

If mindfulness enables awareness of our emotions- (e.g., “I feel stressed, edgy and tired”), then it can either be possible to manage the feelings (rather than avoiding or numbing them). In turn, this can facilitate selection of coping strategies that are more healthy in the long term. This may include talking to a friend, going to sleep earlier, doing exercise, spending less time on social media, practicing a meditation or asking for help, speaking to an employer to let them know about the stress, doing an activity and so on).

A final note

Whilst mindfulness is not a magic bullet, research suggests that it can reduce the symptoms of anxiety and depression and assist with understanding our emotions. Keeping our emotional reasoning in check and practicing mindfulness meditation may be a few strategies to support making sense of our emotions during the transition out of lockdown.

As we begin to have more contact with our family and friends, we can begin to cognize the vast changes to daily life and the communities around us. Whether we either adjust to the eventual end of the pandemic, or, we adapt and adjust to COVID-19 measures being an integrated thread of modern life, connecting to and accepting our emotions may assist us to be ready for any eventuality.