The Baby’s Need for Physical Contact with the Caregiver

- Alessandra Biaggi

- Apr 24, 2023

- 5 min read

Updated: Apr 26, 2023

In my last article, I talked about the importance of parental response to the baby and, in general, of the parent-infant relationship for the infant's long-term development. But what do we mean by the parental response to the baby?

Babies rely completely on their caregivers and have many needs that need to be met. These go from more “practical and basic” needs such as being fed, cleaned, dressed, and changed, to more complex and “psychological” needs such as being cuddled, comforted, held, and touched, and receiving the appropriate-age stimulation so that the baby is kept engaged and attentive but is not overstimulated. These “psychological” needs can sometimes be neglected and considered not as important as the “practical” ones when in reality, these needs are fundamental for the baby's wellbeing and development. In this article, I will discuss the baby’s need to maintain proximity (physical contact) with their caregiver; in my next article, I will talk about the baby’s need to be comforted when crying.

The Need for Physical Contact and Touch: The first nine months of life

One of the most important “psychological” needs for a new baby is being in close, physical contact with their caregiver.

Many readers may not know that the first nine months of life are called "extero-gestation", a term that refers to the period of gestation that occurs outside, following the nine months of pregnancy, which are referred to as "endo-gestation" or "utero-gestation". Compared to other mammals, human babies are born very immature, much before development is completed, because the head can only grow until a certain size in the womb to be able to pass through the birth canal. This does not mean gestation is completed. In fact, during the first year of life, the baby brain doubles in size and then continues to grow significantly, reaching nearly the adult size at 3 years old.

Babies of all species are programmed by nature to stay in contact with their caregivers, as parental proximity ensures care and protection. Furthermore, babies are suddenly born in a bright and noisy environment, which looks very different from the dark and quiet intrauterine world, and they need to eat, digest, breathe and thermoregulate by themselves. Therefore, the first months postpartum are considered a sort of continuation of pregnancy, wherein babies learn to adapt to the new environment. During this first 9-month period, the baby’s need for contact with the caregiver is very high, and then it progressively reduces, although it still remains for at least the first three years of life. Taking care of the baby in a way that resembles pregnancy offers the baby the optimal environment to develop.

There are multiple ways to increase the level of proximity with a new baby, including skin-to-skin contact, babywearing, infant massage, and contact naps. These practices are much more common in many African and Asian cultures, which value extended contact with the caregiver and infant-led separation. For example, babies are carried by mothers for prolonged periods of time and sleep with their parents. In these cultures, close proximity with the caregiver in the first three years of life and beyond is considered normal. In contrast, many Western countries pursue the idea of early physical separation, with the aim to promote the baby’s safety and independence. For example, babies are carried in prams, often stay in baby chairs and are placed to sleep in their cots.

When I was pregnant and was trying to picture how my life as a new mum would be, I thought that a few weeks after delivery, I would have been able to work a little bit on my laptop, while the baby was asleep in the cot. Of course, the reality was different. My daughter would sleep very little in the cot by herself during the day. She would immediately realize when she was not being held in someone's arms anymore. Although I was fully aware that babies need to be close to their parents, I did not know that babies could need so much contact. I continued to keep her close to me during her day naps, telling myself that, if she has this need, I have to respond to it. It was only when I started reading about this topic that I realised my baby was behaving just as many babies do. I realised that what I was doing "by instinct" was the right thing for her at that moment. I relaxed and just enjoyed the time spent with her. With time, she started to sleep in her cot independently.

The Importance and Benefits of Parental Proximity

This need for contact from babies has been demonstrated to be even more important than the need to be fed.

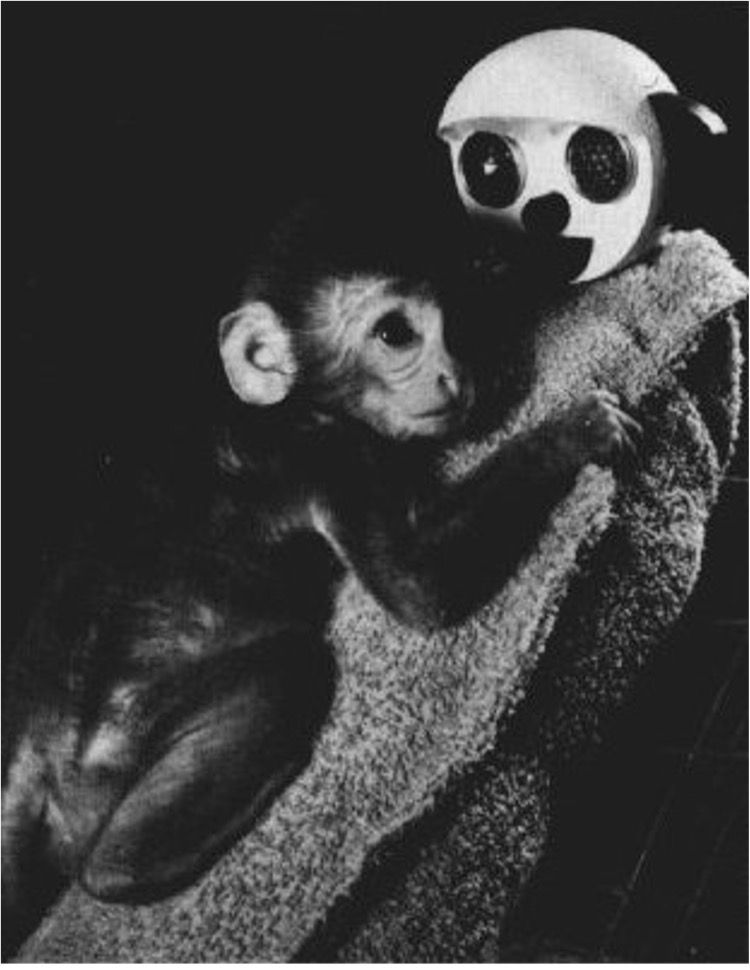

In 1958, in an experiment conducted by the American psychologist Harlow, baby monkeys were separated from their biological mothers and were offered two alternatives: a surrogate mother made of wire and wood who had a milk bottle, and a surrogate mother covered in a soft cloth without any food. Harlow found that baby monkeys preferred the soft mother which provided physical comfort, despite not providing any source of food.

This demonstrated, for the first time, that parental touch and proximity are fundamental for a new baby (in this case, a monkey), and that the relationship with the mother is based not only on the satisfaction of physiological needs but also, most importantly, on the fulfilment of emotional needs.

Since then, many more studies have been conducted, and we now know from an extended body of literature that the experience of touch and proximity not only in the very first hours after delivery but also beyond the immediate postpartum period (for example for the first months/year of life) has multiple long-term benefits for both mother and baby, including infants’ improved quality of sleep, reduced movement and heart rate, less crying and colic problems, better cognitive development, and improved mother-infant interaction, bonding and infant security. In addition, it also lowers maternal depressive symptoms and stress and improves breastfeeding.

Therefore, although responding to the babies’ need for contact can sometimes be highly demanding for a new parent, it is very important for baby development and has positive effects also on parents’ health. In fact, maternal contact and touch function to regulate the baby’s stress response, while maternal-baby separation is associated with increased levels of baby cortisol, the hormone released during stressful situations. Studies conducted in severely deprived children have shown that an extreme lack of contact had a negative impact on babies' development as well as on their immune system, which protects them from infections.

Contrary to what people may think, responding to the babies’ need for physical contact will not "spoil" them and will not obstacle their independence, but rather will help babies independently progress to a new stage of increased autonomy after the first years of life, as they will have gained trust in other people and in themselves. Just as we would not expect a baby to eat solids before the age of six months, to walk before one year, or to speak properly before two years, we also cannot expect a newborn baby to not require physical contact with their caregiver.

In their own time, babies will eventually require less extended contact and be able to console themselves and sleep independently. However, the comfort and reassurance received from physical contact with the caregiver in the very first period of their life will provide the basis for developing security in the world and in themselves.