What Squid Game Reveals About Power, Division, and Being Human

- Aeron Kim

- May 20, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 5, 2025

We are not O or X. We are not built to stay still. Beliefs bend. Allegiances shift. When systems demand certainty, it’s our capacity for change that keeps us human.

When Squid Game first premiered in 2021, it shocked and thrilled the world with its simple yet brutal premise: 456 people in desperate financial circumstances are invited to play deadly versions of childhood games for a ₩45.6 billion prize, approximately £24.5 million (or €29M / $33M). The catch? Losing means death.

It became a cultural event, not just because of its violence or suspense, but because it reflected something deeper: the way modern society divides people, turns survival into competition, and hides control behind spectacle.

With Season 3 arriving this June, I wanted to re-examine Season 1 and 2. International viewers praised its cinematic scale and intensity. But in Korea, reactions were mixed. Why the divide? What is the real message of the show as it nears its conclusion?

The answers lie not just in the plot, but in the shapes, structures, and spaces that define the Squid Game world, and our own.

Understanding Squid Game: For New Viewers

The story centres on Seong Gi-hun, a man weighed down by debt and despair. Along with hundreds of others, he enters a secret competition where participants play traditional Korean children’s games, like Red Light, Green Light or Dalgona, for a massive cash prize.

But failure means immediate death. The games are run by masked guards marked with simple shapes (circle, triangle, square), while a mysterious figure known as the Frontman oversees it all.

The show quickly shifts from a survival thriller into a symbolic narrative about capitalism, social inequality, systems of control and the human cost of competition.

Geometry and Power: Why Shapes Matter

One of the show’s most consistent visual themes is geometry.

The guards are ranked by the shapes on their masks: ● (circle) for workers, △ (triangle) for enforcers, and □ (square) for managers. These aren’t decorative. They reflect status through shape complexity. The more vertices, the more power. At the top sits the Frontman, whose angular mask suggests absolute control.

Even the games themselves are constructed from circles, triangles and squares. And the players? They have no symbol. They’re nameless, powerless, and expendable until perhaps one survives and joins the very system that erased them.

Director Hwang Dong-hyuk described the series as “an allegory of modern capitalist society… a depiction of extreme competition.” But it’s also about who draws the lines and who is forced to live within them.

Controlled Spaces: The Architecture of Fear

The set design in Squid Game isn’t just background. It shapes the story.

In the Red Light, Green Light arena, a painted countryside masks a massive doll and an artificial sky. Only Il-nam, the elderly player who later reveals himself as the game’s creator, looks up. He knows the truth: the sky isn’t real.

Set designer Chae Kyoung-sun described the goal as creating “a sense of disorientation… as if the players were mice in a maze.”

That design echoes a larger theme. The spaces we inhabit in modern life, both physical and social, are often constructed to limit choice and obscure control. In Squid Game, scale and perspective are manipulated to remind players they are small, replaceable, and never truly free.

Drawing the Line: When Rules Decide Who Lives

Squid Game constantly returns to the idea of a line, literally and symbolically.

In the game Dalgona, break the shape’s edge and die. In tug-of-war, cross the line and fall. On the glass bridge, one misstep is fatal.

Lines divide space, but also people. They define who belongs and who doesn’t. In nature, boundaries are fluid. In society, we draw them with precision on maps, between classes, or between ideologies.

Season 2 builds on this idea. It shows how systems that appear democratic, like voting, can be used to divide. Players are asked to vote to quit the game. But the vote is public, labelled and spatially divided. O or X. Red or blue. Once everyone knows your choice, trust erodes. Blame takes over. The game doesn’t need to punish players. They do it to each other.

What should be private becomes a badge of loyalty or betrayal. In this world, freedom becomes performance, and democracy is redesigned as a mechanism of control.

It’s not just fiction. It’s a sharp reflection of today’s polarised political reality, where voting becomes a public test of identity.

Why Korean Viewers Responded Differently

While Season 2 impressed many international viewers, Korean audiences, including myself, were more divided.

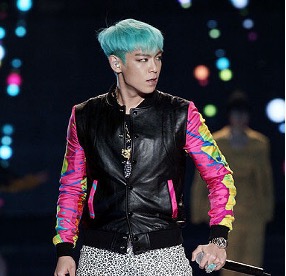

One reason might be the casting. Season 1 featured mostly unfamiliar faces, which made it easier for us to connect with the characters. Season 2 brought in major celebrities. For Korean viewers, actors like T.O.P or Im Si-wan carry strong associations with past roles, making our immersion harder. What felt fresh abroad felt overly familiar at home.

Then there’s the setting. Scenes that may look dystopian to global audiences, drinking vending machine coffee or sitting outside a convenience store, aren’t metaphors in Korea. They’re real. These are everyday spaces tied to economic hardship. For local viewers, the symbolism may have felt uncomfortably close.

Finally, Season 2 leans further into systemic critique. The tension isn’t driven by games, but by public voting, forced group identity, and moral pressure — structures, Korean society knows well. For some, that made the story more powerful. For others, too real to escape into.

Humanism Among the Ruins

Despite its brutality, Squid Game is a profoundly human story. Tender moments stand out: players sharing ramen in the rain, a grandmother gently reminding others to eat when they're hungry, and rest when they’re tired. She becomes a symbol of humanity, a quiet force against the engineered chaos around her.

Another scene shows a player, isolated after a vote, being invited back to eat. “Come eat with us, bro.” It’s a simple line. But it reminds us that your vote isn’t your identity, but your humanity is.

Season 2 Ends in Collapse, but by Design

Season 2’s ending may have felt like a letdown for those expecting victory. But the collapse was intentional. Director Hwang revealed that Seasons 2 and 3 were conceived as one continuous story.

As it expanded, it was split, ending Season 2 at the point when Seong Gi-hun’s hope crumbles.

“Season 2 ends when Gi-hun’s hope is broken. The full message, and the story’s resolution, are in Season 3,” said the director Hwang.

Throughout Season 2, Gi-hun tries every possible path: diplomacy, rebellion, democratic voting, and even external rescue. All of it fails. His closest ally dies. The system prevails.

The season doesn’t offer redemption. It withholds it, making room for transformation. Collapse isn’t the conclusion. It’s the turning point.

We Are Not O or X

As a Korean viewer, I noticed details others might miss. The cultural codes in coffee vending machines, the weight of convenience store tables, and the emotional baggage of casting choices.

But Squid Game is no longer just a Korean story. It’s global. And it reflects how systems divide us intentionally. How democracy can be manipulated. How freedom becomes symbolic. And how, even in small moments like sharing food, showing care, asking “Have you eaten?”, people reclaim their humanity.

We are not O or X. We are stories.

That’s what makes Season 3 so important. This June, Squid Game returns. But it was never just a game. It’s not about who wins. It’s about who we become when the game ends.