Recognising good mental health — more than just a tool for recovery

- Caitlin Pentland

- Dec 18, 2020

- 6 min read

If you could go back in time, what do you wish you had learnt to increase your confidence in navigating your mental health?

Being in my early twenties with several years of lived experience of depression, I can start to empathise with anyone who’s been asking similar questions, both inquisitively and out of despair.

For me, I could identify general facts and figures that would’ve increased my alertness of mental illness, building a fuller picture of what to be aware of… or probably, scared of. But practically, what could’ve equipped me to face my mental health more confidently in the future, rather than being filled with fear and trying to outrun it?

When I’m acutely aware of the current poor mental health I want to escape, I struggle to tangibly recollect and imagine the better mental health I could get close to again. You see, when I had good mental health, I’d never observed or taken note of it, until it had slipped away.

We need to learn to recognise and value good mental health when we experience it, especially pre-crisis, to lay stronger foundations for future fluctuations in our mental health.

Often, when one experiences poor mental health and mental illness for the first time, they learn and recognise more about their mental health, emotions and thoughts than perhaps they had noticed before. Mental illness or declining mental health is already destabilising and strange, and when we have little foundational knowledge about what makes us tick on the better days, it’s like finding our way through unfamiliar roads, when we’re without a map and there’s not a sign to be seen.

In hindsight, I wish I’d been encouraged to learn about my mental health, particularly tuning into what made up my good mental health.

So how would you answer the question: What is mental health?

5–10 years ago, my answer only covered mental illnesses, constrained to predominantly the visible symptoms of the ‘stereotypical teen’ with anxiety, depression or an eating disorder, who met all the diagnostic criteria. It was something that was ‘out there in the world’ but not considered personally.

But mental health is much more than the presence or absence of mental illness. That’s just one dimension. Another dimension includes how well one is able to cope with life, and these dimensions can be related to each other. Models like this one can help me start thinking about the whole space mental health.

Taking you back to how this piece started, I wasn’t aware of how far from ideal my mental health was, until (seemingly) quite suddenly, I was sat in front of my new GP, two weeks into starting my natural sciences degree. In the short 10 minutes, I was patiently listened to, and then, succinctly but empathetically, given a couple of diagnoses, a green paper prescription, and a spot on a talking therapy waiting list.

Personally, the hardest part when starting recovery wasn’t the diagnosis itself, although it was simultaneously a shock and a relief for the grey raincloud I’d been carrying round to finally be given a name.

Neither was it taking multiple tiny pills each day to help rebalance my chemistry (less fun than popping out chocolate from an advent calendar, but more essential in my case!), or knowing that I needed therapy to get to a better headspace. (Of course, I can’t take for granted the encouragement, tough love and absence of judgement from my family and network of friends, which I am immeasurably grateful for.)

For me, the hardest part was trying to imagine, and recall, how my life could be, and probably was once, less grey.

Better mental health was clearly the goal, but I didn’t know how that could happen for me. It’s a little like if I asked you to conceptualise a completely new colour — different to all the hues available in the existing visible spectrum, one that can’t be mixed from pots of primary coloured paints. Success?

I can cautiously guess that over the years, my poor mental health had developing, slowly taking up space, pushing out and shouting over the things which were perhaps good for my mental health. It was as if almost everything I did, whether it was academic work or extracurricular activities, was laced with the common fear of my efforts not being enough.

Anything I could possibly ‘fail at’ petrified me, and stopping short of overworking seemed too lazy to bear. Check out Courtney’s piece on perfectionism and mental health here.

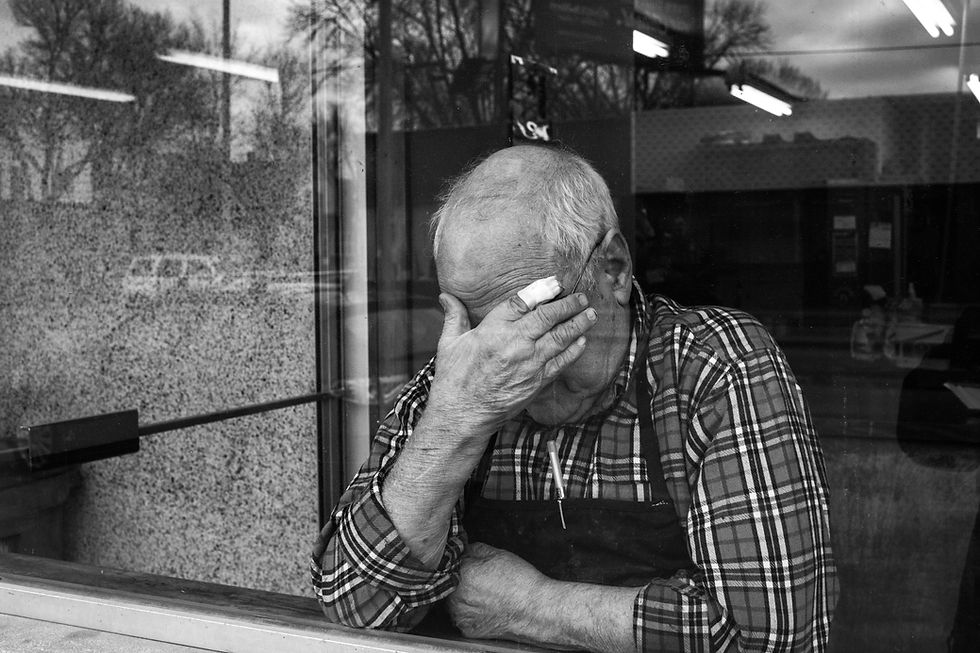

When battling poor mental health and mental illness, it can be a challenge to do anything more than just survive, since you are living in an all-consuming situation.

Often, part of getting your mixture of emotions and behaviours ‘back on track’ will be doing things that you enjoy, providing momentary relief from inside your head, and building up your wellbeing as a whole.

Perhaps that could be picking back up a hobby, reconnecting with some friends, getting a good amount of sleep, exercising, and eating well. But when you’re in the midst of struggling, having the capacity and stamina to know where to start with these things, let alone do them, is a huge challenge. It’s difficult to recall positive memories, to have the imagination to think about ways of helping yourself, to have any confidence about your recovery and to regain self-worth when you have less motivation. I found myself becoming fearful that nothing would ‘work’, inevitably leading to me having more evidence that I am a true failure and a fraud, so maybe it was safer to just hibernate in survival mode.

Like most people, my sleep and appetite felt like they were part of the vicious cycle, being disrupted by mood, and then the lack of them weakened my ability to cope with my mood.

Friendships felt fragile, despite being supported and encouraged, because I was afraid of being a burden.

The idea of doing something just because I enjoyed it was both unimaginable and scary, because, over the years, everything was done out of an intense need to be ‘productive’ — forming an intricately controlled coping mechanism.

I’d fallen out of practice of doing the things that were good for my mental health, and following what seemed like easy advice to ‘go for a walk, try painting or bake something’ felt impossible, requiring time and attention that was already fully engaged in preventing my mood from tumbling even lower.

The possibility of expending a little energy re-adjusting my grip, since I was weak and already slipping, seemed logical, but, in the moment, was outweighed by the fear of falling and not being able to get back up.

Consider the benefit your normal activities and interests may be providing for your mental health.

For example, recognising that when you run, in addition to keeping you agile and gaining competitive Strava stats, it gives you the headspace to process your emotions in a safe space.

Or when studying, in addition to making your family proud and gaining a qualification, it gives you confidence as you master the workings of a corner of the universe.

When time gets tight later in life, you’ll be better equipped to decide what prioritise and why, by having an explored what helps your mental health in the good times.

Affirm and reflect the positive and supportive elements in our friendships.

We know how important social connection is in supporting individuals with poor mental health. But, as we’ve seen, talking about mental health, across the whole spectrum from good to poor, could help us to recognise the support we have, before one of us needs it.

Normalising everyday conversations around our mental health could help reduce the pressure for there to be a ‘big enough reason’ to talk about it, in all its forms.

Practise putting into words (consciously thinking, writing or speaking) what you are grateful for and what you are proud of yourself for.

By reinforcing and dwelling on some of the good in our lives, we’re not being big-headed or pretending that everything’s perfect, we’re just being real and letting ourselves appreciate that. Even if worries spring up, you feel a little silly, or some days you can’t seem to think of anything.

It doesn’t matter how small or seemingly trivial your points are. You’re not trying to change the world, you’re simply tuning into what our fast-paced, results-driven, comparison-prone culture often doesn’t give time to do.

We’re edging closer to the point where mental illness can be spoken about without shame or fear. Let’s also not forget the whole picture of mental health, recognising it’s something we all have, even without or before mental illness. Treatment is life-saving for many people, and there is yet more research to be done, but without recognition and sustaining of good mental health, the burden of poor mental health will be almost intolerable.

Your mental health should matter, both during crisis and without crisis.

Notes:

A book about mental health that I absolutely love by the Clinical Psychologist, Dr Emma Hepburn @thepsychologymum — A Toolkit for Modern Life: 53 Ways to Look After Your Mind

Other blogs mentioned

o Why Perfectionism May Be Damaging for our Mental Health — Courtney Worrell

Blogs I also learned from (not linked in text)