Wearable Technologies: The future of healthcare?

- Faith Matcham

- Aug 29, 2022

- 4 min read

Recent estimates forecast that 1 billion people worldwide will be using wearable devices to track their levels of sleep and activity by the end of 2022. Even the most basic smart watches and fitness trackers can provide insight into daily hours of sleep, number of steps taken and heart rate, and with increasing investment in the wearable electronics sector, more advanced technologies are becoming progressively affordable and accessible.

I am a lecturer in Clinical Psychology at the University of Sussex, and I have been involved in several projects in the field of digital health, often representing significant partnerships between private and public sector organisations.

My first glimpse into this world was during my post-doctoral position based at King’s College London in the Remote Assessment of Disease and Relapse — Central Nervous System (RADAR-CNS) project.

RADAR-CNS was a major international research project aiming to investigate the utility of remote measurement technologies (specifically wearable devices and smartphone sensors) to refine outcome measurement and predict outcomes across three central nervous system disorders: Epilepsy, Multiple Sclerosis and Major Depressive Disorder.

But before I talk more about my research experience, let me discuss about wearable devices in general health!

Can these devices can be used for more than just general fitness and sports training?

Absolutely! The benefits of the real-time monitoring facilitated by these devices are beginning to be realised in healthcare research and services.

Pairing this wearable device data with data collected from inbuilt smartphone sensors can provide a rich insight into our health and patterns of behaviour we’ve never seen before. This can allow us not only to track and monitor changes in health over time, but also to improve our ability to predict outcomes in long-term illnesses, track changes in response to treatment, and provide more timely, personalised interventions.

In an under-resourced, over-burdened healthcare system, the move to digitalise medical care is inevitable, and a digital transformation has been well underway for decades. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated this evolution– with country wide lockdowns having pushed aspects of our lives, such as our education, employment, relationships and healthcare services, online.

The responsibility, for businesses, researchers, clinicians, healthcare providers, funders, and regulators, is to ensure the digital transformation is fast, effective, inclusive, thoughtful, meets the needs of the people using it, and, critically, is evidence based. However, this, unfortunately, is not always a given.

A recent review of digital health companies found that 44% of these businesses had zero evidence of clinical robustness. Furthermore, there was no association reported between the clinical robustness of the company and total funding, suggesting that a clear evidence-based approach may not be a priority in the funding of digital health solutions. Therefore, developing this evidence should be a first and foremost in everyone’s minds.

RADAR-CNS Major Depressive Disorder project (RADAR-MDD)

RADAR-CNS was pioneering in this approach of using remote measurement technologies — as well as representing clinicians, researchers, engineers, computer scientists and bioinformaticians from all over the world. It prioritised patient and public involvement, open science (creating an open mHealth platform for the collection and processing of mHealth data: RADAR-base), and clinical utility.

With its own integrated Patient Advisory Board, RADAR-CNS pioneered the inclusion of people with lived-experience throughout the research process. This insight is critical to ensure that the technologies, that we as scientists are working hard to develop and test, really meets the needs of the people we’re trying to support.

In parallel, incorporating the voices of clinicians in the development of novel technologies is essential for maintaining engagement with professionals and understanding the intricacies of implementing new technologies in clinical settings.

Our key findings

RADAR-CNS, and RADAR-MDD specifically, taught us all a lot about the capabilities of remote measurement technologies in the context of Major Depression (define). Although the funding for the programme has finished, we are still writing research papers now and have already published some of our key findings. We found that…

1. People are motivated to participate in remote measurement studies.

One of our first papers arising from RADAR-MDD described the amount of data we collected throughout the study, and our recruitment and retention rates throughout the course of follow-up.

We had very high retention rates, with 80% of participants continuing in the study until the end of follow-up. Participants wore their Fitbit for approximately 15 hours per day, and an average wear-time of 62% across a median follow-up time of 541 days (approximately 18 months).

2. Having depression does not stop people from engaging with these kinds of technology.

Our recent paper published in the Journal of Affective Disorders examined the associations between symptoms of depression, anxiety and functional disability and i) perceptions of the usability of the technology and ii) the amount of time people spent wearing their Fitbit and the number of app-based questionnaires they completed.

We found extremely small differences, indicating data collection via remote sensing is robust across depression, anxiety and functional disability severity.

3. There are associations between data collected via remote measurement technologies and depression outcomes.

We have published papers showing associations between a range of parameters measured within RADAR-MDD and depression severity. In particular, we have reported associations between depression outcomes and homestay, mobility, Bluetooth connectivity, and sleep patterns.

Questions still to be answered

Despite the progress made in the field through this study and many others, there are outstanding questions which remain unanswered:

Can this technology provide something of personal value to the patient?

Might having access to one’s own health data inadvertently increase health anxiety, increase inappropriate help-seeking behaviour or even trigger a deterioration in symptoms or relapse?

Can we improve self-management and a sense of empowerment over an otherwise unpredictable illness?

How do we make sense of what the data mean, and what actions should be taken in response to it?

How can we integrate high-volume data usefully into our existing healthcare infrastructures without over-burdening already over-worked healthcare professionals?

If risk is detected via the online system, such as an adverse event related to treatment, who’s responsibility is it to intervene?

Who “owns” the data, and how much data is too much data?

The future of healthcare is digital, and it’s our responsibility as researchers to address these open questions and ensure that digital healthcare is implemented thoughtfully, conscientiously, and ethically.

— — —

Watch Faith discuss key RADAR-CNS findings, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M1peYybtvU0&t=6s

RADAR-CNS was jointly led by King’s College London and Janssen Pharmaceutica NV. The project was funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative. Find out more: https://www.radar-cns.org/.

— — —

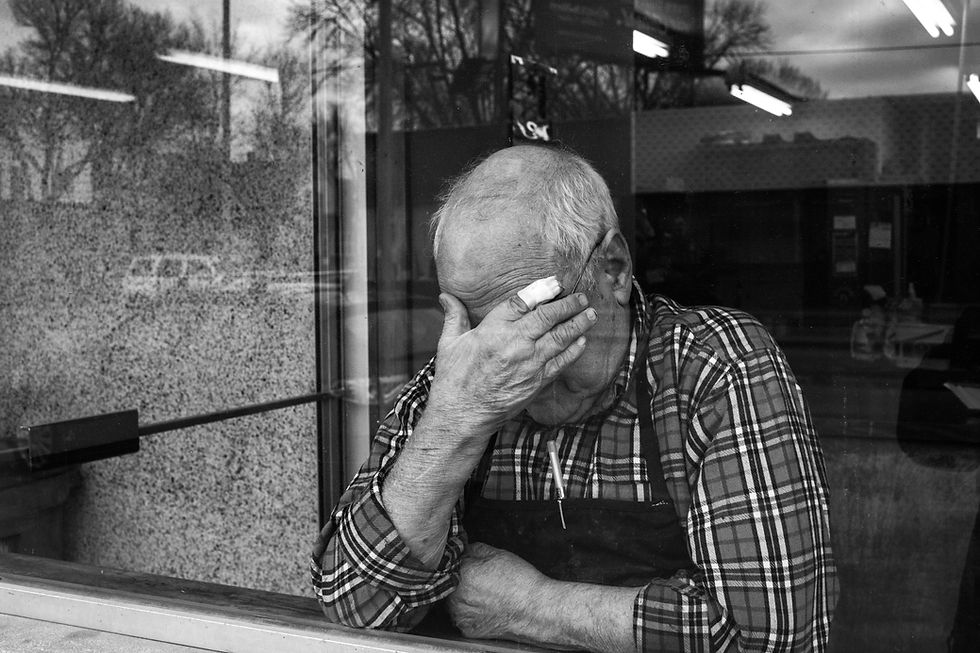

Header image by Artur Łuczka on Unsplash