Beyond the Veil of a Male Phenomenon: Sex hormones & the immune system in suicide vulnerability

- Giulia Lombardo

- Apr 6, 2022

- 6 min read

Updated: Jun 27, 2023

Beyond the Veil of a Male Phenomenon: Sex hormones & the immune system in suicide vulnerability

Trigger warning: The following blog contains discussions about suicidal ideation and explicit descriptions of suicide itself. Some readers may find this distressing.

“I used to think it utterly normal that I suffered from “suicidal ideation” on an almost daily basis. In other words, for as long as I can remember, the thought of ending my life came to me frequently and obsessively.” — Stephen Fry

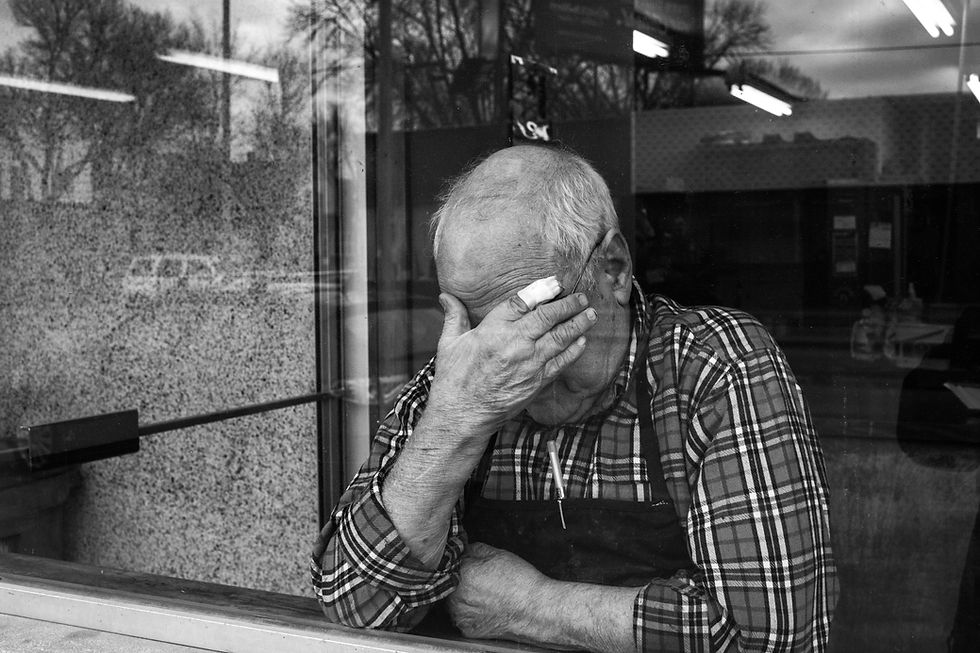

Losing someone to suicide can bring pervasive feelings of guilt, persistent questions about if anything could have helped them, and continuous scanning of their last days to understand the reasons behind their suicide. The feeling of helplessness can be disarming, and there are several support groups for the relatives and friends of suicide victims.

Death by suicide is one of the leading causes of death worldwide, with more than 700,000 completed suicides every year (the World Health Organization (WHO)). Thus, early prevention is crucial for both sides, those at risk of suicide and those who remain. However, despite the high rates, this multi-stratified phenomenon is still taboo nowadays.

There are a few definitions and degrees of ‘severity’ that you need to be familiar with before approaching this topic in the context of research. These are suicide itself (that is, “death caused by self-directed injurious behaviour with intent to die”), suicide attempt (“non-fatal, self-directed, potentially injurious behaviour with intent to die”), and suicidal ideation (“thinking about, considering, or planning suicide”).

Suicide is such a delicate topic, and it can be viewed from different perspectives: personal, philosophical, political, cultural, psychological, and so on. In this blog, I will focus on my research, mainly exploring biological mechanisms and clinical aspects that are possibly relevant to increased suicide risk, which I recently described in my paper “New frontiers in suicide vulnerability: Immune system and sex hormones”.

Approaching this topic from a biological perspective might feel quite dehumanising and detached, however, it might give us the possibility to unravel underlying factors which can increase suicidal vulnerability. I think it is essential to highlight new potential pathways in research that could help us identify those at high risk of suicide, detect new ways to help those who experience suicidal ideation, and perhaps even prevent suicide.

I am a PhD student at King’s College London, and my main interest has always been the dialogue between biological and psychological aspects of mental health, especially major depressive disorder (MDD). I believe that the study of biological dynamics in psychiatric illnesses will help in creating a sex-specific medicine and tailored treatments to offer the best rehabilitation pathway for those patients in need.

Suicidal ideation is one of the core symptoms of depression, and mood disorders such as MDD are the most common psychiatric conditions linked to suicide risk. Suicide has been linked with alterations in some of the brain areas involved in decision making, emotional regulation and behaviour control.

However, some aspects of depression differ between sexes, so a priority in research is to detect and explore these dissimilarities. Even though women are at higher risk of both developing MDD and showing suicidal ideation than men, men are more likely to complete suicide. As a result, male sex has been identified as a suicide risk factor, along with previous suicide attempts and the degree of depressive symptoms (National Register Based analysis).

Why does it happen? Can research help us understand increased rates of suicide among men?

Immune system, sex hormones and suicide risk

To understand why these biological factors are so important in depression and suicide, let’s look in more detail at this topic.

The immune system plays a major role in some patients with depression. Briefly, patients with depression have increased levels of immune biomarkers (“a biomarker is a molecule, gene, or characteristic by which a particular pathological or physiological process, disease etc., can be identified.”) associated with increased immune system activity. Patients who do not respond to common antidepressants (i.e., treatment-resistant depression (TRD)) have even higher levels of these biomarkers than those who do respond, with TRD also being associated with increased suicide risk. As well as depression, increased inflammation seems to be a suicidal-specific biological trait. In fact, depressed patients who attempted suicide have increased inflammatory biomarkers than depressed patients without suicidal ideation.

Furthermore, sex hormone levels are altered in patients with increased suicide risk. Increased androgen levels (e.g., testosterone) in both sexes and decreased estrogen levels in women are associated with increased rates of completed suicides and suicide attempts. Additionally, one of the possible immune-modulatory mechanisms might be played by sex hormones. In fact, estrogens can have both anti- and pro-inflammatory properties, whereas testosterone mainly has anti-inflammatory effects. Nevertheless, the balance between estrogen and testosterone might be important in regulating the immune system. Thus, an interplay between sex hormones and the immune system may be present in suicidal patients, and specifically in patients who attempted suicide.

Some evidence suggests a possible role of these two systems in suicide. However, you are here to read about why these two systems may make suicide a “male phenomenon”, and why research should focus on them both. So, let’s continue.

Where does the link between male sex and increased suicide risk lie?

Violent methods of suicide show a link with increased inflammation, which is higher than in non-violent suicide attempts. Generally, men tend to use violent (and therefore more lethal) methods to complete suicide, while women tend to use non-violent methods.

Other factors and sex differences must be considered when discussing suicide risk. For example, aggressive behaviour is linked to increased androgens, and impulsivity to increased inflammatory biomarkers. Interestingly, Mann and colleagues (2014) found an association between violent suicide attempts and both impulsivity and aggressive behaviour in men.

However, we don’t have to fall into error and focus only on the biological aspects of suicide. In fact, there is more to reveal beyond the veil of this phenomenon. Clinical characteristics in males can help us understand further why men are at a higher risk of completing suicide.

There is a need to increase awareness about sex differences in mood disorders and suicidal traits

The time of intervention is crucial in these situations. However, it is not always possible to carry out rapid intervention, the chance of which dramatically decreases when the duration of the suicidal process (from the onset of the suicidal ideation to the act) is short. This suicidal process seems to be a male-specific risk factor, which is shorter in men than in women.

Understandably, males with mood disorders can be more irritable, and importantly, they can have decreased impulse control. Furthermore, men tend to appear more hesitant than women in seeking help when they experience depression. Thus, there might be a delay in the diagnostic process, and the likelihood of therapeutic treatments is reduced.

What can you do?

I think there is an extreme need nowadays to learn and share as much information as possible about differences in clinical aspects of depression between men and women. Most of all, informing the public opinion about depression in men might help men to come forward, communicate their realities and thus, receive the support they need. Increased awareness may help us recognise when our loved ones need support, even if their presentation may not look like our typical understanding of depression. Consequently, this can enable us to help those in need feel understood and welcomed.

The interaction between sex hormones, immune system, and behavioural aspects in males and females is worth investigating. However, although several studies investigate the interplay between these two biological systems, only a few focus on MDD and even fewer on suicidal patients. There are simple associations that are inadequate to reach causal conclusions, so more studies are needed to investigate the mechanisms behind suicide risk, particularly in men. The final aim of this research would be to offer new sex-specific therapeutic treatments and preventive strategies, and develop sex-sensitive services for patients who are at risk of suicide.

“In the case of suicide, people think that no fight was involved they merely think that the person couldn’t take it and felt weak. They forget all the mental struggles the person faced because they were invisible and sometimes unspoken and unexposed to anyone. This attitude of society is wrong.” — Deeksha Arora

If you are struggling and in need of support, below are a few incredibly helpful organisations that provide both resources and direct help:

Shout Crisis Text Line — you can text Shout to 85258 if you are experiencing a personal crisis, are unable to cope and need support.

Talk to the Samaritans — they offer 24-hour emotional support in full confidence. You can call them for free on 116 123

CALM (Campaign Against Living Miserably) offers a chat and hotlines service from 5pm to midnight

Papyrus (Suicide Prevention Charity) offers similar service for adolescents and young adults under the age of 35

Mind — you can call the Mind Infoline on 0300 123 3393 / info@mind.org.uk, the Mind Legal Advice service on 0300 466 6463 / legal@mind.org.uk