What Prison Taught Me About Mental Health

- David Shipley

- Nov 28, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: Apr 29, 2025

Before being sentenced to prison, in February 2020, I had a long time to imagine it. In 2014, working in corporate finance, I committed fraud, lying to an investor with whom I was starting a company, and producing a fake document to support that lie. Years passed, and no one unearthed the lie, but still, I worried every day. Then, in early 2018, the police contacted me. I gave an interview that spring where I confessed everything and waited.

In the autumn of 2018, they charged me, in the spring of 2019 I pleaded guilty at Southwark Crown Court, but it wasn’t until almost a year later that I was sentenced to 45 months. While in jail, I became a writer and learned a great deal about myself. Now, three years after my release, I’m writing this piece to explore how prison affected my mental health, and what I learned there.

The long wait for sentencing meant I had years to worry and think about prison. When I woke each morning there would be a moment before I remembered. You’re going to prison. Then the cold spike of fear through my chest. I felt in a constant state of readiness, wanting to flee the danger, being unable to do so. As a result, my mental health worsened. I drank heavily, suffered pits of yearning despair, and seriously considered suicide.

Even before this stress, I’d struggled. After an awful time at my prep school, aged seven, I hid myself. For the longest time I’d hidden who I was, feeling that the real me wasn’t worthy of love. This suppressed tension affected all the relationships I tried to form, and spilled over into the rest of my life. I found so many other people and their behaviours frustrating. A slow driver, a delayed train, or an unhurried pedestrian would infuriate me.

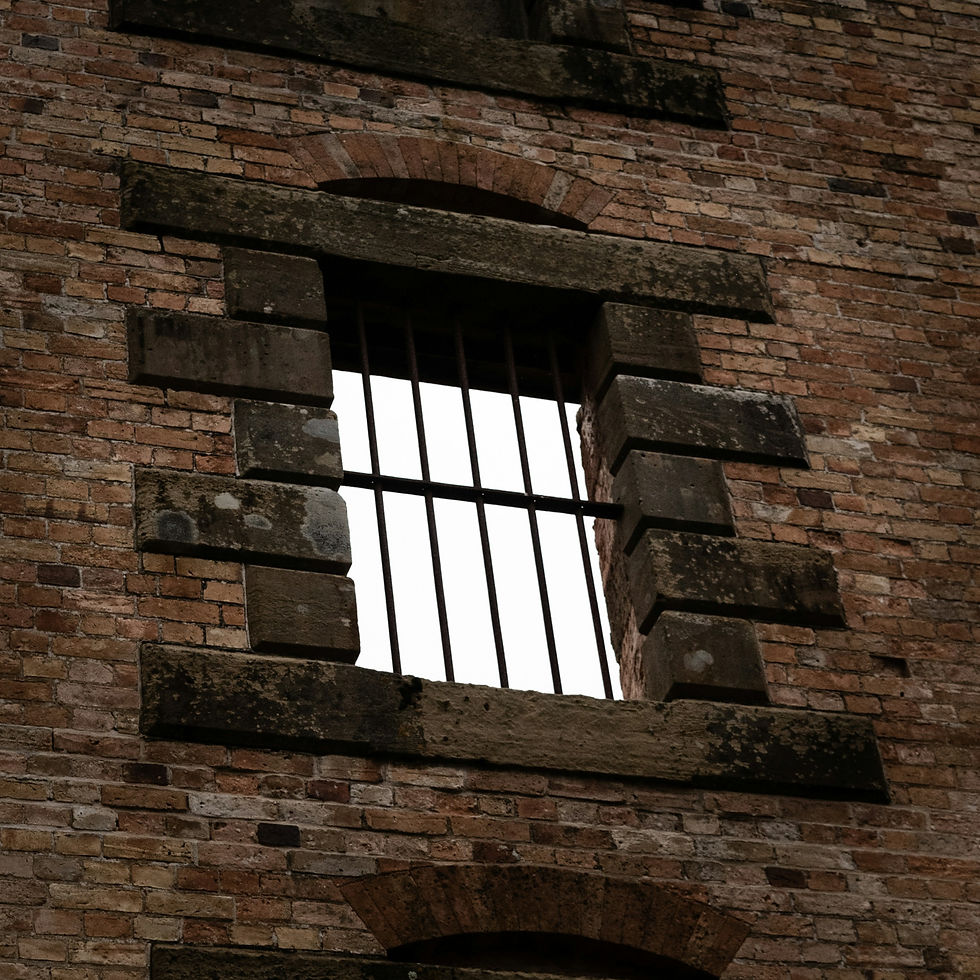

Our prisons are not places which are good for mental health. This is most obviously shown by the ‘safety in custody’ statistics published by the Ministry of Justice. The latest figures show that 88 self-inflicted deaths took place in the twelve months ending September 2024, and 13,605 prisoners self-harmed, a total of 76,365 times over the course of that year. In reality, this will hugely understate the real number. While I was a prisoner, I saw many men who would quietly self-harm and hide the evidence. Poor mental health among prisoners is seen in countless other ways. During the day, many of us had the distractions of time in the exercise yard, work or classes, and the relentless noise of the wings. At night, when the pounding of feet and clanging of doors and clunking of locks was over, when we were all locked away, men would scream or sob or yell or tear their cells apart.

And then, on the 26th of March 2020, the first COVID lockdown began. We were locked inside our cells for 23, or sometimes even 24 hours a day. Food brought to our cell doors, we spent day after day in concrete tombs the size of a car parking space. Deprived of social interaction, of variety and of purpose, it’s no wonder many of us struggled and suffered.

How did I cope? I wrote. I began a fantasy novel about a boy who grew to become a monster. I wrote in my journal every day. I thought about those I loved. And I remembered. I remembered the choices I’d made which led me to prison. In the quietness of my cell, particularly in the dark at night, without devices, without social media, and without distraction, I had to face myself. Again and again, I considered my life, reflecting on the moments when I could have chosen differently, and imagining what might have been. I gazed upon my crime, and my own failings, and accepted entirely and completely that I only had myself to blame. My poor moral choices were my own, and there was no meaningful support available from mental health professionals or chaplaincy staff.

I learned to accept what I couldn’t change. Prison is very good for that. There is so much out of your control. When will the cell door open? When will they feed us? How long will the water be off? Will there be electricity this evening? Will the phones work? I realised that if I became frustrated by every setback or problem which I could do nothing about I would spend my entire sentence being frustrated. And so, after months of prison lockdown, I realised I’d stopped being irritated. I discovered that while I may not be able to control events, I can control how I react to them. "Irritated" isn’t something which is done to us, it’s an experience that we create within ourselves.

While jailed, I saw so much pain. I met men who’d had terrible lives, who’d been abused as children, who’d suffered in ways no one should suffer. Adults who have spent time in the care system are vastly overrepresented in the prison population, with almost a quarter of adults in prison having been in care at one point. Many prisoners struggle with literacy; over 60% of prisoners can’t read at the level expected of an 11-year-old. I found it very easy to understand why someone like this might deal drugs or steal in order to survive. As I watched the men around me and listened to their stories, my compassion for them expanded. I had no excuse for my crime, but so many prisoners had experienced childhoods which left them with little choice or hope. I came to understand that many people we meet are battling pain and monsters of their own, and rarely is the behaviour we might find challenging about us.

I was released from prison in August 2021, and although I carry the horrors of prison with me, I’ve never been happier or calmer. How did this happen?

I accepted my absolute responsibility for my actions and choices. I have agency and am able to control much of my life. However, I also recognised that much is beyond my control, although my responses to events are mine to choose. I became more compassionate, seeing each person in the world as one who may be suffering or struggling. Finally, I developed a deep sense of proportionality. When you’ve been in prison, a delayed train or a traffic jam seems less important.

I wouldn’t recommend prison for personal growth. It’s an awful place and I saw things there I will never forget. But I do believe those lessons of responsibility, acceptance, compassion, and proportionality can be learned without time behind bars, and that they make for a happier and healthier life.

This article has been sponsored by the Psychiatry Research Trust, who are dedicated to supporting young scientists in their groundbreaking research efforts within the field of mental health. If you wish to support their work, please consider donating.